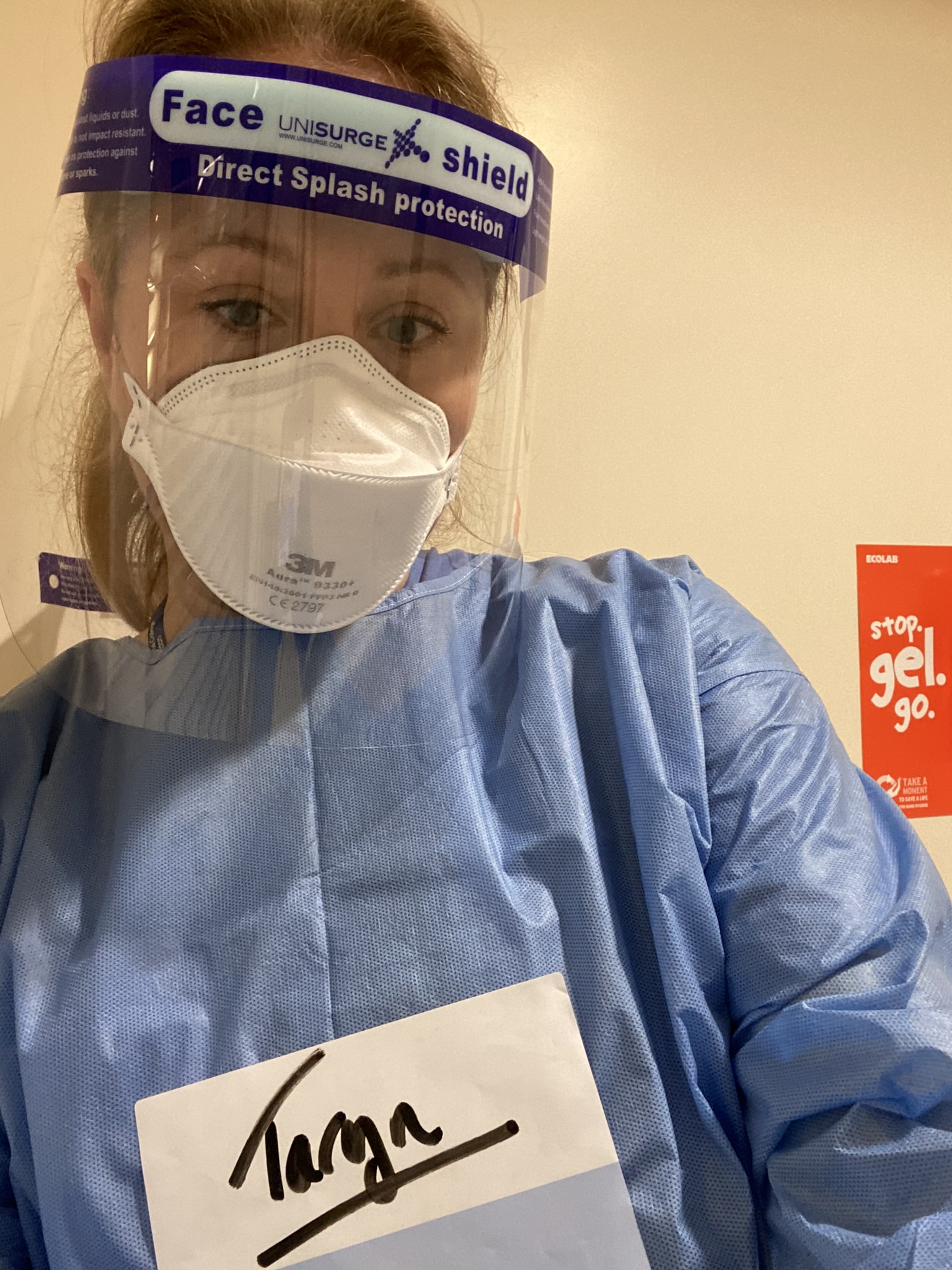

Dr Taryn Youngstein

In the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 as doctors watched scenes of overwhelmed hospitals, first in China and then Italy, rheumatologist Dr Taryn Youngstein had a particularly unique insight into what was to come.

The London-based specialist was one of a group of clinicians tasked with advising public health authorities in the UK on the idea of shielding patients with rheumatic disease. “For me the whole thing changed at that point,” she said. “That was in February [2020] so there was minimal COVID-19 transmission in the UK. Being told we were thinking about shielding patients was a shocking concept.”

Dr Youngstein, who is based at Hammersmith Hospital and is an honorary clinical senior lecturer at Imperial College London, was subsequently involved in writing the British Society of Rheumatology guidelines on shielding the most vulnerable, including developing their risk calculator, and at that point she was very worried about her patients because no one really knew what COVID would mean for them, she explained.

Her day-to-day work changed very early on, quickly moving to remote clinics, dealing with patient concerns and collaborating with colleagues about how to manage new referrals. But unlike some medics she was not redeployed in the first wave. Instead, as a principal investigator in the COVACTA study looking at the use of tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia, she was going into critical care in full PPE to recruit patients. At the same time she kept her usual clinics going – albeit in a different way – and saw new and urgent patients face to face. Prescription systems rapidly changed. It was a huge amount of work.

“We did manage to keep rheumatology services running the whole time. We were very concerned with the logistics of bringing people in so it was very controlled,” she added. “Patients were very very anxious about coming into hospital and they still are, and I don’t think that’s unreasonable.”

Playing a multitude of roles

From a personal point of view, as a working parent in a two-medic household, figuring out key-worker places and suddenly having no other childcare was incredibly stressful, she said, describing a 7 am dash to [retailers] Marks and Spencers to buy food for the family when the store opened early for NHS staff. “They all clapped and gave me a free Percy Pig Easter egg. It did make you realise that we were going to work in a hospital and at that point it did feel like a personal risk and no one really knew what would happen.”

By May and June when COVID rates came down there was still no let up, Dr Youngstein says. Some colleagues became ill and so clinics had to be covered, while catching up with routine work and providing rheumatology guidance to an expert multidisciplinary group on clinical management of COVID patients at her large NHS trust, which is based across three sites. “It has been an incredibly busy time,” she said.

When the second wave hit, Dr Youngstein was redeployed into intensive care. From the start of January to the middle of March she was doing shifts helping to care for the sickest COVID patients doing both nursing and medic roles, from changing beds to drawing up meds, and tracheostomy care. “You were a junior doctor and a nurse all in one,” she said. “We just sort of muddled through together.” While doing these shifts she created a ICU family liaison team to which she recruited rheumatology consultants and doctors from other specialities – including some who were shielding – to help make daily phone calls to relatives of those who were intubated in ICU.

All this while keeping her rheumatology clinics going with phone consultations on her day off – something she said she was only able to do because she is not normally full time – and doing the ICU MDT meetings five days a week. There were points at which it was overwhelming, she admitted.

But she realised from before the first COVID case was diagnosed in the UK that rheumatologists would have a key role in providing expertise on the treatments that may end up helping patients, and that her experience with anti-rheumatic drugs such as tocilizumab would be needed. She is also now a co-investigator on the MATIS trial, assessing whether hospitalised patients with COVID-19 respond better to the addition of fostamatinib or ruxolitinib to their standard of care.

Looking ahead

More than a year on from when she was first asked to take part in those high level discussions about the prospect of shielding her patients, and with a vaccination programme well under way, she said rheumatology has several large challenges to face.

“One thing I really want to stress is that while research in COVID is really important, we have a responsibility to our patients to keep research in rheumatology happening despite the pandemic,” Dr Youngstein said. “I have a lot of respect for more senior colleagues who kept that going. That might have seemed non-urgent at the time but it’s really quite important.

“The other thing is our junior doctors have been incredible throughout this, so mature, and redeployed before anyone else and some of them have missed their pure rheumatology training.” She added that training in general – for doctors and specialist nurses – will be a big challenge with some trainees not having had face-to-face exposure to patients.

“The other thing is our junior doctors have been incredible throughout this, so mature, and redeployed before anyone else and some of them have missed their pure rheumatology training.” She added that training in general – for doctors and specialist nurses – will be a big challenge with some trainees not having had face-to-face exposure to patients.

It alludes to the challenge facing the NHS in general when Dr Youngstein explained that despite never ‘closing’, she now has an 11-month wait for follow-up appointments. Overall in rheumatology departments throughout the country there is a massive backlog, which must now be managed against a backdrop of ongoing infection control and social distancing.

“An 11-month wait is unrealistic and so all my clinics are overbooked,” she said. “I’ve booked out my annual leave 18-months ahead and put in these ‘firebreaks’ where if you need to move patients around there would be these weeks where you could do it.”

There is going to have to be a period of working out what is the best, safest and most efficient way to manage patients, she said. “I’m very worried about patients who don’t speak English or who have learning difficulties and how they’ve fared with phone consultations, and some very elderly patients who have struggled to access services over this time.” Going forward, she added, she prefers to see all patients face-to-face unless they themselves prefer a phone appointment.

“I’m hoping we will be able to return to normal, but a new and improved normal.”