A breakthrough in identifying the neurobiological basis of apraxia of speech has been made by an international team of researchers led by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne.

Researchers led by MCRI speech pathologist Professor Angela Morgan have used MRI to identify anomalies in a key speech pathway of the brain that could help neuroscientists develop more targeted treatments for children.

The most persistent and severe speech articulation disorders, apraxia of speech may be due to defects in one of two parallel neuroanatomical models of speech processing. The dorsal stream is involved in sound to motor speech transformations, while the ventral stream supports sound/letter to meaning.

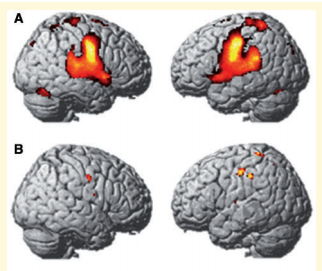

In a study involving a family with hereditary childhood apraxia of speech, the researchers conducted functional MRI imaging during speech in seven of the children. Combined with brain tractography analysis, this showed they had large grey matter reductions over the left temporoparietal region, but not in the basal ganglia, relative to typically-developing matched peers.

In a paper in the journal, Brain, Prof Morgan described how the team also detected white matter reductions in the arcuate fasciculus (dorsal language stream) bilaterally, but not in the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (ventral language stream) nor in primary motor pathways.

MRI imaging during speech for a healthy control (A) and a child with apraxia of speech (B)

“Our findings identify disruption of the dorsal language stream as a novel neural phenotype of developmental speech disorders, distinct from that reported in speech disorders associated with FOXP2 variants,” they wrote.

In early childhood, the immature dorsal route is immature and projections from auditory and sensorimotor maps to feedback control maps are believed to undergo progressive tuning.