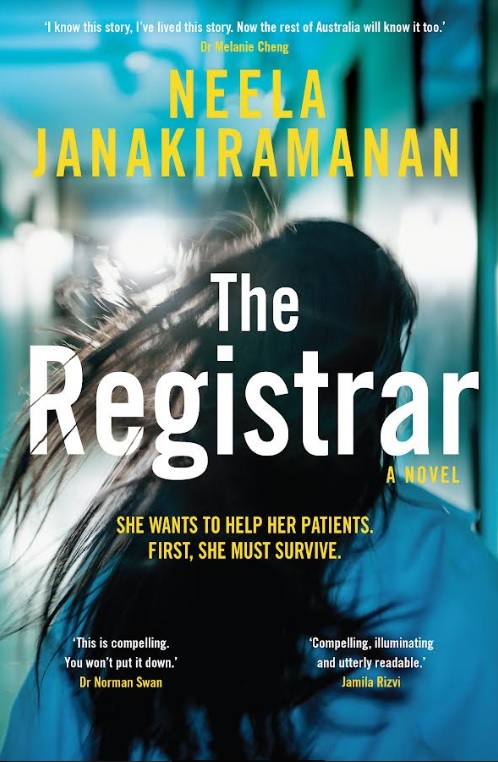

In her debut novel, Victorian reconstructive plastic surgeon Dr Neela Janakiramanan shares the story of the dedicated and ambitious Dr Emma Swann, who is about to start a gruelling year as a surgical registrar at a prestigious hospital.

In her debut novel, Victorian reconstructive plastic surgeon Dr Neela Janakiramanan shares the story of the dedicated and ambitious Dr Emma Swann, who is about to start a gruelling year as a surgical registrar at a prestigious hospital.

Drawing on her own experiences, Dr Janakiramanan relates her character’s challenges and offers a rare insight into the competitive and exhausting world of surgical training.

Below is an edited extract of The Registrar, out now.

The child’s hand is grey and mottled. I’ve crouched down next to the bed to examine it and now I stand up, the urgency of Ngoni’s phone call clear. We went to medical school together and he’s not often rattled, certainly not by a simple trampoline accident. He’s correct, the right forearm definitely has no pulse.

‘We took him straight to X-ray,’ Ngoni says as he pushes a computer on a trolley into the room. He points at the screen, confirming the severity of the fracture.

Shit.

‘What’s going on?’ the mother asks, her voice shaky, the tear stains on her cheek matching those of her child. She’s looking at Ngoni. He waits for me to explain.

‘He’s broken his arm just above the elbow and the fracture’s putting pressure on an artery. But don’t worry,’ I reassure her, ‘as soon as the bone’s straight again, the blood flow will return to normal.’ I have one eye on the clock above the bed. ‘What time did it happen?’

I don’t tell her that muscle cells deprived of blood start to die within a couple of hours. I don’t tell her that if it takes too long to restore blood flow then the muscles can swell within their tight fibrous coverings and die even hours or days later. In years past, kids with this fracture developed clawed fingers and permanent disability—and the best way of avoiding this is to straighten the bone and unkink the artery as soon as possible. I don’t want to tell her that this is a time-critical emergency until I have a plan.

‘I think . . .’ The mother can’t remember how long it’s been. She didn’t check the time when her son cried out. She didn’t look at her watch as she pulled him out of the narrow gap in the trampoline netting and called an ambulance.

Ngoni shuffles some papers and extracts a pink sheet. ‘The ambulance arrived at 11.03,’ he says.

‘They came quite quickly,’ the mother adds.

I check the time again. It’s already 12.30.

‘And when did he last have something to eat or drink?’

‘I made him and his sister a strawberry milkshake around ten.’

I sigh. The anaesthetists are going to love that.

‘Can you . . . ?’ I start, but Ngoni’s already nodding. He’ll explain what’s going on to the mother while I organise an operating theatre. We don’t have much time. I tear off some ID stickers with the boy’s name, still on their paper backing, and run.

These corridors are familiar to me. Down the hall, up a flight of stairs and then around the corner—the operating theatres are located directly above the Emergency Department. I can plan what to do next while I’m moving.

Mei Ling is the surgeon who’s on call. She’s the first person I have to tell. I’m just the junior doctor covering for Orthopaedics today. Sure, I’ve worked on surgical teams for years but I won’t even be a trainee surgeon for another three weeks and then it’s a further five years to be a surgeon. I’m not allowed—nor qualified—to demand an operating theatre, no matter the urgency of my case. I try four times. Mei Ling doesn’t answer her phone.

Shit.

I decide to organise a theatre anyway and then worry about a surgeon. Surely someone will be around.

‘Woah, Emma, slow down!’ Ibrahim puts his arms out to stop me with a laugh; I’ve almost bowled straight into him and his team on the stairs. He was my registrar four years ago when I first started working as an intern. I’m still grateful for his patience—medical school teaches us how to perform CPR but not how to treat conjunctivitis.

‘Sorry, Ibrahim, I’ve got a supracondylar with a dying arm,’ I say as I rush past.

‘Good luck!’ he echoes back, a floor away already.