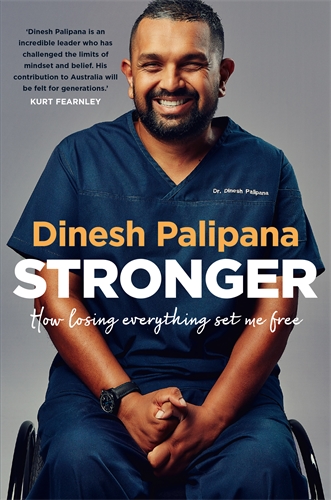

A puddle of water on a highway changed Dr Dinesh Palipana’s life forever. Halfway through medical school, Dinesh was involved in a catastrophic car accident that caused a cervical spinal cord injury. After his accident, his strength and determination saw him return to complete medical school – now with quadriplegia. Dinesh was the first quadriplegic medical intern in Queensland, and the second person with quadriplegia to graduate medical school in Australia.

A puddle of water on a highway changed Dr Dinesh Palipana’s life forever. Halfway through medical school, Dinesh was involved in a catastrophic car accident that caused a cervical spinal cord injury. After his accident, his strength and determination saw him return to complete medical school – now with quadriplegia. Dinesh was the first quadriplegic medical intern in Queensland, and the second person with quadriplegia to graduate medical school in Australia.

Despite all of the pain and hardship he’s faced, Dr Palipana now sees his accident as a turning point for the better in his life. He believes it has made him a better doctor, with a better grasp of the concerns and fears of his patients, and a more sensitive, open human. He fights for equal and equitable access for disabled people, and is a compassionate and skilled doctor working in one of Australia’s busiest hospitals.

After everything he’s been through, Dr Palipana believes he is now happier, stronger and more capable than he was before the accident. It helped him to clarify what is important in his life, and taught him that happiness and strength can always be found within.

Below is an edited extract of Stronger, out now.

I had no cash reserves when I started as a doctor. I used my credit card to buy some business clothes and shoes, and spent that Saturday and Sunday feverishly preparing to start work on Monday. My mind was so prepared to be unemployed that the idea of starting work took a bit of getting used to.

I was due in the hospital early on Monday. I woke up at the usual ungodly hour to get ready. This day, I wasn’t catching a tram as a student, but as a doctor.

I arrived at the hospital for orientation. It was scary. Starting work as a doctor is scary for anyone; the idea of having someone’s life in your hands, even under strict supervision as a baby doctor, is nothing to be sneezed at. Doing that with quadriplegia just amplifies the nerves.

The media came to cover my first day. They asked me how I felt. ‘Excited, but terrified!’ was my answer. Some of the journalists had taken the whole journey with me, so we were all happy to see that day come to fruition.

We spent two weeks in orientation, which covered things like prescribing, referrals, ward rounds and other basic topics that the medical intern should be able to do. There were also the tick-box exercises mandated by human resources. Some of these were pointless online activities, often to mitigate a risk that has appeared on a bureaucrat’s radar at some point. No one learned anything, but the organisation can say that their staff was trained in whatever topic it was – usually at a significant cost.

I also had to complete training that other doctors didn’t need to do. I sat in a room for the better part of a day learning about occupational violence and its management. The hospital thought that I was at higher risk of experiencing violence.

The hospital and I then planned how I was going to tackle the year and complete the necessary rotations to gain full registration. A key question for me was which medical specialties to do. That involved a conversation with a doctor who looked after the interns.

He was a good man, but an occasionally intimidating one. It wasn’t unusual to see him storming around the hospital yelling profanities about subpar management by other doctors. Still, he had a heart of gold. We set up a meeting. He said to me, ‘We need to do this year in a way that is not tokenistic, not too easy, and has credibility.’ There are some specialties well known for having less than vigorous workloads. I was not to spend too much time in those specialties.

We decided on psychiatry; obstetrics and gynaecology; vascular surgery; general medicine; and extended time in emergency medicine. Vascular surgery in particular was known to be a spirited specialty. But I was going to be starting in psychiatry. Just as in student life, it had a better pace for me to get used to being a doctor. In contrast to being a student, though, I had actual responsibility now.

During my time in psychiatry, I was still figuring out how to do some things. As an intern, many tasks were new to me. But sometimes the problems came from unexpected quarters. I had a colleague who was just barely my senior on our team. From very early on, they stopped talking to me. If I said good morning, there was no reply. They often didn’t share the patient list with me. They didn’t discuss what was happening with our patients. Most of our interactions were filled with awkward silences, with them not responding to anything I said. I still have no idea what that was about. I must have got them offside at some point. I loved the work, but dealing with this colleague every day wasn’t fun. I tried to ignore it and keep going. I just needed to get through the internship. To my relief, the psychiatry term quickly came to an end.

Everything is a big step in early intern life – even prescribing paracetamol. What if I cause liver failure? What if the patient has a reaction? When I had days off, I was terrified that I would come back to find that some monumental error had killed someone.

This is not far-fetched. In a moment of vulnerability, one doctor told us about losing a young patient to a pulmonary embolism. Ever since he lost the patient, that doctor has been extra vigilant about pulmonary emboli. Medicine does that. When we make an error, we swing far the other way to being overcautious, sometimes to the point of detriment. My colleagues have experienced the sudden loss of paediatric patients, adult patients, and even people they have known personally. The marks left by these losses are deep. Imagine carrying the death of someone with you.

As an intern, you learn more about the medical hierarchy. The medical student is more insulated because they have little responsibility. The intern is responsible for things, and they answer to those above them. Those above aren’t always forgiving. Ryan Holiday said in his book Ego is the Enemy that, ‘It is a timeless fact of life that the up-and-coming must endure the abuses of the entrenched.’ In medicine, the entrenched wield power not just by virtue of seniority, but by the influence they have on a junior’s career. They can make or break it.

There are also power differentials between specialties. Radiology, for example, is at the end of the line. Everyone needs something from them, but radiologists rarely need anything from anyone else. Therefore, requests to radiologists can be met by snappy rebukes. Emergency medicine refers patients to every specialty. Other specialties, apart from general practice, rarely refer to emergency medicine. This creates a power imbalance that sometimes results in difficult conversations. The way people behave in situations of perceived power differentials sometimes shows the dark side of the human nature.

To me, since I was a student, the emergency department was always a good society fostered by great leadership. They employed a flat hierarchy. Consultants were happy to be called by their first names. This created an environment in which an intern could approach the consultant without fear. In some other specialties, the unspoken rule for an intern is never to contact the consultant directly. I’ve seen a breach of that rule result in retribution affecting a person’s entire intern year.

Even though the emergency physicians were great to their interns, the interns couldn’t be shielded from the harshness of other specialties. One night, for example, I was sitting next to another intern in the emergency department. It was late; approaching midnight. An ambulance accidentally delivered a terminally ill young cancer patient who was actually intended for a private hospital to our emergency department, and the intern assumed care of them. The patient was normally looked after in that private hospital, who had all their records. The staff there were familiar with them and knew what this patient needed to be comfort- able. The family hoped to arrange the prompt transfer of this young patient to the private hospital so they could be somewhere peaceful and familiar, away from the chaos of an emergency department.

The intern called the private hospital. The nursing staff there were happy to accept the patient. However, the on-call oncologist needed to accept the transfer. Those were the rules. So, the intern called the on-call oncologist. Nearly immediately, I heard their screaming response over the phone.

‘I don’t give a f*** about this patient. They belong to another oncologist. Don’t ever f***ing do this again,’ they shrieked, and continued with a long tirade full of expletives. They refused the transfer.

The intern cried. They finished the shift, then cried some more in the car park. The patient stayed in our emergency department till the morning, until another on-call oncologist started at the private hospital. This type of thing is sadly too common in medicine.

Medicine isn’t easy. Aside from the weird social structure within, the technical demands of the job are high. Mistakes can kill people. Chaos can ensue within seconds. We are thrown into complex situations regularly, without warning. Training is long and arduous.

While medicine is criticised for these things, I think there is some basis for the way it is structured. The hierarchy is necessary, because at the end of the day someone needs to be responsible for the patient. If there is an adverse event, the responsibility often falls on the person at the top of the food chain. Why wasn’t the surgeon adequately supervising their junior? Why didn’t they double-check the order? Most problems become the responsibility of the senior-most doctor.

Training needs to be long and arduous, because at the end of the journey you are going to be that senior-most person. People will look to you for a decision. You will be responsible for everything, including the lives of multiple patients simultaneously.

For all its complexities, though, I love being a doctor. The opportunity to be challenged, to learn every day, to grow, and to do all that while helping someone is a unique privilege. Medicine humbles me daily. It teaches me to be a better person, much through my interactions with the humanity within it.

Later on, when I was doing the intern term in general medicine, administrative tasks were common. Many of the general medicine patients had complex social issues. They didn’t fit neatly into another specialty like cardiology. Therefore, there was a lot more going on than medicine alone. It was easy to get caught up in the mundane tasks of the day, forgetting why we were there – the patient.

One day, I was leaving work after a long day in general medicine. It was early evening. I was tired. Just as I exited the ward, a nurse ran after me.

‘Are you finishing up?’ the nurse asked. ‘Yeah, I’m just leaving.’

‘That’s okay then. The family of that terminally ill patient just wanted to talk to a doctor. I can get the ward call doctor.’

I knew that the ward call doctor wouldn’t know this patient. At night, the ward call person looks after a large number of patients. They often tend to minor tasks like recharting medications. They don’t assume the ideal continuity of care for a patient like this.

I stopped at the door for a minute. I had a choice. I was off the clock; I could leave and forget about the whole incident. Or, I could go back and talk to the family about where we were at. I had the ability to explain everything clearly as a doctor from the treating team. I knew that the family would benefit from a chat with a doctor familiar with the patient. I went back. The family were grateful.

That moment at the door allowed me to reflect on something that I haven’t forgotten to this day. For me, that was just another day at work with many patients. For that family, it was one of the biggest events that they’ll go through in their entire lives. We’re faced with these choices all the time. Do we decide to be a human or a drone?

When I rotated into the vascular surgery department, the days became much longer. Ward rounds started anywhere from 6.30 am to 7.30 am. For me, that meant waking up between 3 and 4 am.

The vascular surgery team liked to have an evening ward round too. There were three junior doctors on our team, so we took turns staying back on alternate days. Some days, I didn’t get home till 9 or 10 pm.