The family of a Brisbane gastroenterologist who took his own life has implored people to talk more openly about suicide.

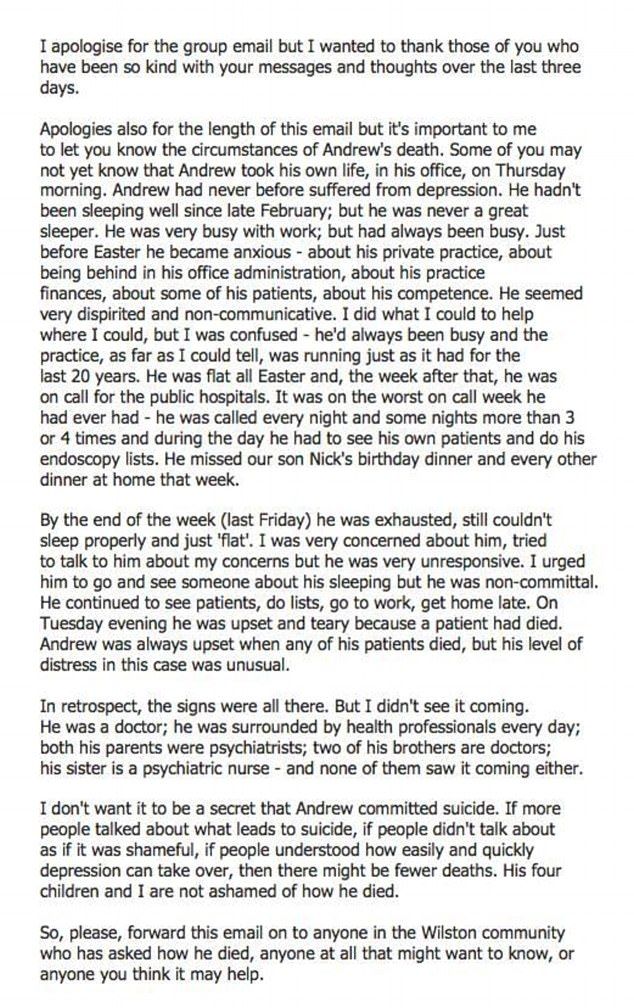

A letter made public by Dr Andrew Bryant’s family said in the months prior to his death he was anxious ‘about his private practice, about being behind in his office administration, about his practice finances, about some of his patients, about his competence’.

He was also busy. ‘It was on the worst on call week he had ever had – he was called every night and some nights more than 3 or 4 times and during the day he had to see his own patients and do his endoscopy lists,’ said the letter written by Dr Bryant’s wife (see below for full letter).

And he was exceptionally distressed by the death of a patient.

“I don’t want it to be a secret that Andrew committed suicide. If more people talked about what leads to suicide, if people didn’t talk about as if it was shameful, if people understood how easily and quickly depression can take over, then there might be fewer deaths,” she wrote.

Dr Kairi Kolves, Principal Research Fellow at the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention (AISRAP), told the limbic that work-related problems were more prevalent in suicides by doctors than other professionals and the general public.

Data from the Queensland Suicide Register between 1990 and 2007 had shown doctors were the most likely group of 25-64 year olds to be affected by work pressures and the least likely to be affected by relationship problems.

“However work related problems can impact on family life and family can impact on work,” Dr Kolves said. “It is easy to say aim for work-life balance but it’s not easy if you have to do night shifts.”

Dr Kolves said more recent research had also highlighted that work-related access to lethal means was a risk factor for suicide.

The research concluded there may be a need for different interventions for males and females.

Dr Kolves said doctors would also be susceptible to the impact of traumatic events.