A national shortage of palliative medicine physicians is leaving tens of thousands of terminally ill patients without adequate end-of-life care, figures suggest.

The ageing population is driving demand for services, with a 10% year-on-year increase in MBS-subsidised palliative care services in the five years to 2015.

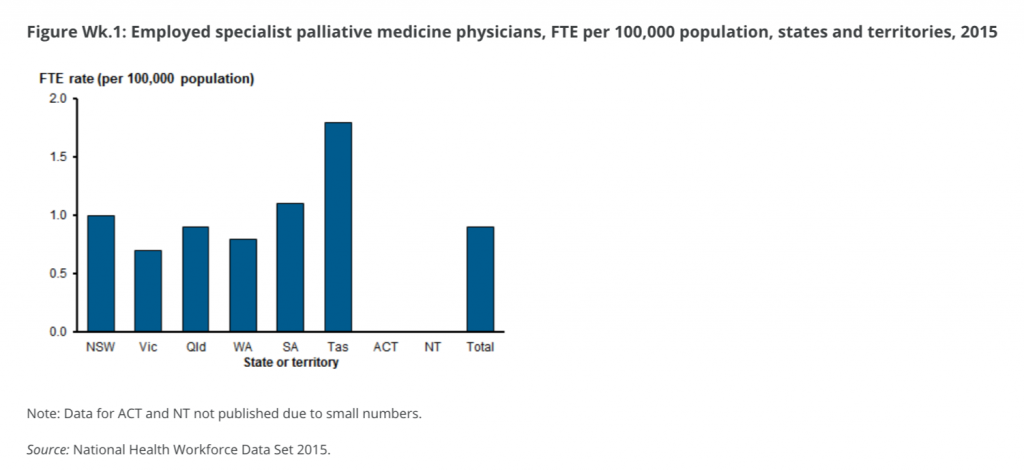

Expert groups are warning that demand outstrips supply with a national workforce of just 213 palliative care specialists, representing an average of 0.9 FTE per 100,000, less than the minimum recommended by the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine.

The situation is dire, according to Palliative Care Australia (PCA), which has called on the federal government to urgently fund more specialist trainee positions.

There is one palliative medicine physician for every 740 deaths [per year], PCA says in a pre-budget submission, which calls for the appointment of a palliative care commissioner and a national strategy.

The access problem is worsened by uneven workforce distribution, with 84% of specialists working mainly in major cities. State-to-state distribution is also uneven, with Tasmania having a ratio of 1.8 FTE specialists per 100,000, while Victoria has just 0.7.

This means for many “access to community-based palliative care is determined by where they live, rather than where they would prefer to die”.

PCA chief executive Liz Calligan says an estimated 80,000 people are missing out on needed palliative care annually.

“We have around 160,000 deaths per year, and three quarters are expected from malignant or non-malignant chronic disease.