Clinical practice is always based on the best evidence available at any given time. However, the recent American College of Physicians (ACP) gout guidelines have caused an uproar. To find out why, the limbic spoke with Professor Kevin Pile, Director of Medicine and Rheumatologist at Campbelltown Hospital. “Generally, guidelines are meant to provide you with clear pathways of what to do – that is who do you treat and when. The ACP guidelines are controversial because they are a little bit vague,” explains Prof. Pile.1

Good tools, poorly applied?

When it comes to gout, there are effective treatments available, but management of the disease remains suboptimal.2 “Indeed, gout is very badly managed in the community. We still see lots of emergency department attendances and hospitalisations, and despite recommendations from expert rheumatological bodies like the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), patients continue to have frequent, disabling attacks of gout. What tends to happen is that patients become despondent as their current urate lowering treatment is not effectively preventing attacks of gout which occur with increasing frequency and severity, and they are just dealing with the symptoms when they arise. And that’s just what the ACP guidelines continue to promote – treat to control symptoms – rather than treat-to-target to prevent long-term joint damage,”2 notes Prof. Pile.

Professor Pile continues, “One important thing to remember is that each attack is not benign.3 There is evidence to suggest untreated gout leads to an increase in the number and severity of flares and structural damage.3 What the ACP advocates is a reduction in symptoms rather than treating to protect the joint.4 Their expert panel of primarily primary care physicians came to this conclusion due to the type of evidence they considered as compared to other bodies. The ACP guideline points out deficiencies in evidence-based, randomised-controlled trials.4 Taking this purist view, it is possible to come to the same conclusion as the ACP. However, given there are no long-term randomised, controlled trials that compare treated versus non-treated patients with gout and given results from real-world, observational studies exist that an sUA target of <0.36 mmol/L can be established – it is surprising they were not taken into consideration.3 The challenge is a lack of robust evidence to demonstrate the reduction in flare-ups and structural damage. It is likely the reduction in uric acid levels is going to be different for each person.”

What’s the evidence for treat to target vs treat for symptom control?

Urate-lowering therapy is a necessity to avoid flare ups. There is indirect evidence from the pre-urate lowering days, where patients who had no effective urate-lowering therapies experienced an increased number and severity of flares and developed structural damage as a result of the development of tophi.3

When it comes to a treat-to-target approach, the debate has largely centred around how low to go. What is the ‘target’? The answer seems to be as low as is required to dissolve crystals – which is not only low enough to prevent symptoms but underlying joint damage as well.3 The challenge in its implementation is that is expected to be different for each patient, although a minimum target of 0.36 mmol/L has been suggested.3

The ACP guideline discourages the use of long-term urate lowering therapy in most patients based on inconclusive evidence to support the serum urate target approach – which is largely based on expert opinion and clinical experience.3 According to Perez-Ruiz F et al. the lack of clarity provided by the guideline regarding in whom and when to initiate long-term urate-lowering therapy has the potential to cause hesitation and risks ongoing joint damage if urate crystals persist in the serum.3 They also note that with clear recommendations and an appreciation for prevention of underlying damage asymptomatic disease may be causing, other specialist-led guidelines continue to endorse management that tackles the underlying pathophysiology.4

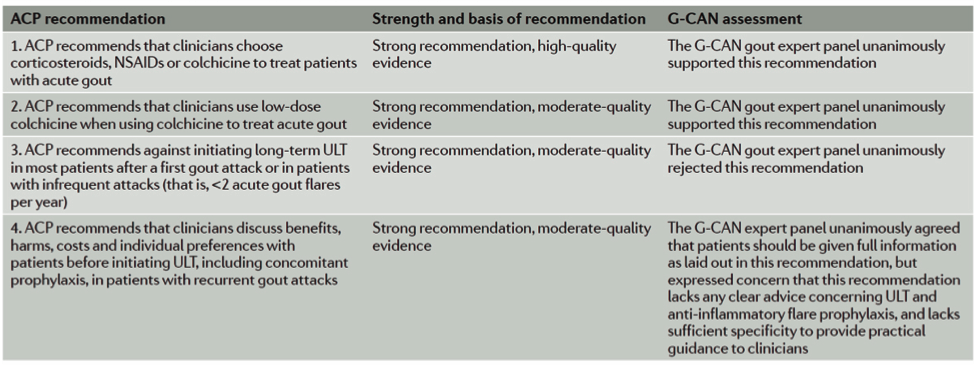

INFOGRAPHIC:

Key recommendations from ACP on the management of acute and recurrent gout and summary of Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) position4

Adapted from Dalbeth N et al. 2017.2 ACP, American College of Physicians; G CAN, Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network; ULT, urate-lowering therapy.

Indeed, looking at the ACP guideline, it is challenging to determine which patients require subsequent therapy. Prof. Pile recommends, “it shouldn’t be “in most patients”. The guideline should be explicit in who and when you should treat. For example, in a young 25 year-old patient who presents with their first attack and profound hyperuricaemia is certainly going to have recurrent attacks. In other patients you need to consider the severity and impact of the presentation – is it an acute attack in one joint lasting one day, or was it multiple joints resulting in hospitalisation, or are tophi developing, or kidney stones? Considering the impact of the attack is important.” By examining the clinical situation in each patient,

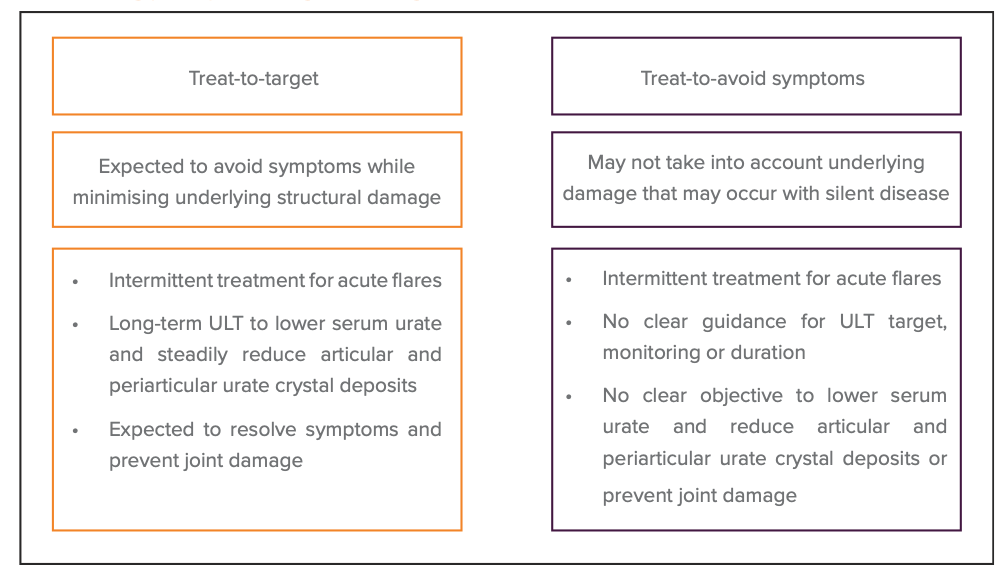

Treat-to-target versus treat-to-avoid symptoms are expected to have different clinical-pathologic outcomes2

INFOGRAPHIC/BOX:

The differing perceptions of gout management2

Adapted from Dalbeth N et al. 2017.2 ULT, urate-lowering therapy.

“In those who need urate lowering treatment, a start low and increase slowly to achieve the required level of urate lowering is desirable. This is because the final urate lowering dose is individualised for each patient, using the minimum dose in that individual to achieve a serum urate that will dissolve urate crystals in joints, skin, and kidneys. Treating to a target is logical for patients and brings about symptom control and prevention of damage,” suggests Prof. Pile.

Where to now?

Given all recent guidelines had access to the same evidence, but interpreted their value differently, emerging and future studies will likely be the means to resolve the dispute. As noted by Dalbeth et al., this “…will enable alignment and consensus in guidelines for primary care physicians, rheumatologists and other specialists involved in management of patients with gout.”2 It is an opinion shared by Prof. Pile, who concludes, “In Australia, we’re driven by evidence-based medicine and a balance between minimising side effects for patients and treating to cure.”

This article was sponsored by Menarini, which has no control over editorial content. The content is entirely independent and based on published studies and experts’ opinions, the views expressed are not necessarily those of Menarini.

References:

- Gout doubt: experts challenge new ACP guidelines. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/871265 (accessed 7 June 2018).

- Dalbeth N et al. Nat Rev Rheum 2017;13:561-568.

- Perez-Ruiz F et al. Rheumatol 2018;57:i20-i26.

- Qaseem A et al. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:58-68.