The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) has raised the issue of whether the definition and diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD) needs to be refined.1 “One problem has been that existing guidelines pre-dated our current understanding of the clinical and pathological evolution of PD,”1 explained Thomas Kimber, Clinical Associate Professor in the School of Medicine, Adelaide University and Consultant Neurologist and Head of the Movement Disorders Service of the Neurology Unit, Royal Adelaide Hospital at the Teva Central Nervous System Weekend (TCW 19). In his lecture, A/Prof. Kimber walked the audience through some key recommendations from the MDS and what they mean for the clinician.

“It is well recognised that the first time we see the patient they have had the disease for some time already” – A/Prof. Kimber

A/Prof. Kimber discussed some of the limitations of the existing criteria for diagnosis of PD, a main challenge being the lack of acknowledgement of pre-clinical and prodromal disease. “We now know that patients presenting to a doctor with motor symptoms of PD will have had pathological changes developing for some time – initially with no symptoms (‘pre-clinical phase’) followed in many cases by non-motor symptoms, such as constipation and REM sleep behaviour disorder (‘prodromal phase’),” he explained.2 “The existing diagnostic criteria limit the diagnosis of PD to the motor-symptom stage and do not accommodate the pre-clinical or prodromal phases.”2 He also explained that the MDS has recommended that the necessity of a motor syndrome be retained in the definition of PD, while at the same time highlighting the need for biomarkers that will allow future diagnosis at a pre-motor stage. “Clearly defined criteria to assist in the early identification of PD is where we want to get to, so that we can be in a position in the future to offer neuroprotective/disease-modifying therapies before motor symptoms begin. The MDS has been working to remove the hurdles that limit the management of patients who may be at an earlier stage of disease.1 But at the moment, for a definitive diagnosis of PD, motor symptoms are still the benchmark.”1

There’s a need to un-complicate the definition of PD

The MDS task-force also raised several other potential short-comings of the current definition of PD.1 One of these is the requirement for the presence of alpha-synuclein pathology in order to make a pathological diagnosis of PD, bearing in mind that we now know that several genetic causes of PD (e.g. autosomal recessive PD due to PARKIN mutations) lack alpha synuclein pathology.3 The Task Force also foreshadowed a potential change to the distinction between the diagnosis of ‘Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD)’ and ‘dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)’, which currently hinges on the interval between the diagnosis of PD and dementia (> 12 months being indicative of PDD and < 12 months being indicative of DLB).1 “The Task Force suggested it might be sensible to utilise the term ‘Parkinson’s disease dementia’ for any patient fulfilling criteria for a diagnosis of PD who also has dementia. The diagnosis ‘dementia with Lewy bodies’ could then be applied to patients who have a cognitive phenotype typical of DLB, but who lack a motor syndrome sufficient to make a diagnosis of PD. This would basically do away with the somewhat arbitrary 12 month rule,”1 A/Prof Kimber said.

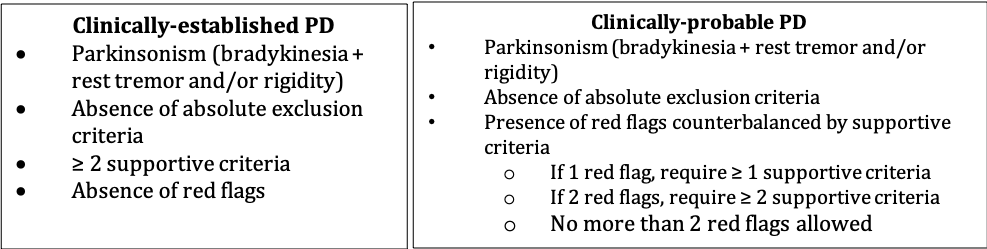

On the issue of the diagnosis of PD, A/Prof. Kimber explained that a separate MDS Task Force has recommended that two diagnostic categories of PD be adopted (‘clinically-established’ and ‘clinically-probable’), based on:4,5

- the level of clinical evidence in support of a diagnosis of PD, and

- the extent to which other conditions that can present with Parkinsonism can be ruled out.

These criteria are helpful for the clinician and are of particular importance for researchers enrolling patients in clinical trials and include:4,5

Research into the management of motor symptoms of PD highlights improvements in some areas, but gaps remain

A/Prof. Kimber then shared key findings of the recent MDS evidence-based review on the treatment of motor symptoms in PD.6 Reviewing literature published up to the end of 2016, A/Prof. Kimber discussed the increase in the number of therapies for motor symptoms. The greatest increase in therapies has been in treatments for motor fluctuations. These include novel ways of administering existing medications, such as levodopa (e.g. extended release levodopa-carbidopa), as well as adjunctive therapies that, when used in combination with levodopa, smooth motor fluctuations and increase “on time”.6,7 Aside from pharmacotherapy, the other stand-out in terms of adjunctive therapy was physical exercise.8 “The data affirms the benefits of physical exercise and resistance-based training in optimising motor function in PD,” he noted.

However, we are still lacking treatments that prevent the onset or delay the progression of disease – for me that’s the outstanding unmet need right now,”6 he concluded.

This article was sponsored by TEVA, which has no control over editorial content. The content is entirely independent and based on published studies and experts’ opinions, the views expressed are not necessarily those of TEVA.

References:

- Berg D et al. Move Dis 2014;29(4):454-462.

- Olanow CW, Obeso JA. Mov Dis 2012;27(5):666-669.

- Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mov Dis 2010;25(0 1):S32-S39.

- Postuma RB et al. Mov Dis 2015;30(12):1591-1601.

- Postuma RB, Berg D Int Rev Neurobiol 2017;132:55-78.

- Fox SH et al. Mov Dis 2018;33(8):1248-1266.

- Hauser RA et al. Mov Dis 2014;29(8):1028-1034.

- Corocos DM et al. Mov Dis 2013;28(9):1230-1240.