Lunch symposium at the Endocrine Society of Australia Virtual Seminar 2021

At this year’s annual Endocrine Society of Australia Virtual Seminar, Amgen sponsored a lunchtime symposium on bone building therapies for osteoporosis on Saturday, 1st May. Chaired by Dr Cherie Chiang (Consultant Endocrinologist at Melbourne Health, Austin Health and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Chemical Pathologist at the Royal Melbourne and Alfred Hospitals), the symposium featured Professor Michael McClung, the founding director of the Oregon Osteoporosis Center. 275 attendees gathered virtually to learn about the role of osteoanabolic therapy as well as its efficacy and safety. What follows are the highlights of Professor McClung’s presentation.

Antiresorptive and osteoanabolic therapies for osteoporosis

Professor McClung began by outlining the main treatment goal in osteoporosis; to reduce the risk of fracture. There are now multiple therapies with different mechanisms of action that work to achieve this, with international guidelines recommending treatment selection based on individual fracture risk.1–4

Medications for osteoporosis fall into two main categories: antiresorptive and osteoanabolic.5,6 Table 1 summarises their main differences.

Table 1. Osteoporosis treatment options in 2021.5,6

| Mode of action | Examples | |

| Antiresorptive agents |

|

|

| Osteoanabolic agents |

|

|

Osteoanabolic therapies

Professor McClung’s presentation then focussed on the two osteoanabolic agents currently available in Australia, teriparatide and romosozumab.7,8

Beginning with a summary of their dosing, duration, route and frequency of administration, Professor McClung noted the “important clinical logistical differences between the two drugs”. Teriparatide is given at a dose of 20 µg by subcutaneous injection, which can be self-administered once daily.7 Duration of therapy is from 18 to 24 months. Romosozumab is given at a dose of 210 mg, as two subcutaneous injections once a month. Duration is approved for 12 months of monthly dosing.8

Fracture risk reduction of osteoanabolic therapies

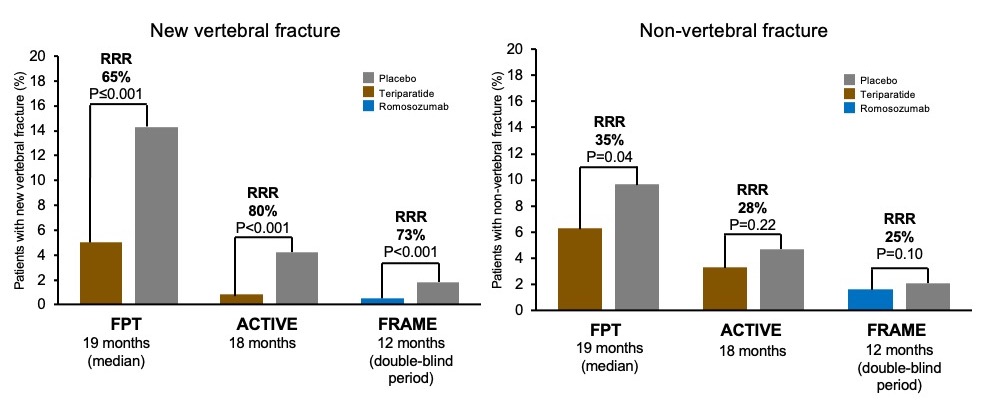

While studies of teriparatide and romosozumab have assessed fracture as a key endpoint, the efficacy outcomes of the 3 placebo-controlled trials cannot be directly compared, as the study populations were quite different, evidenced by the fracture rates (Figure 1). Teriparatide was assessed in two trials – the Fracture Prevention Trial (FPT) and the Abaloparatide Comparator Trial in Vertebral Endpoints (ACTIVE trial). Romosozumab was compared to placebo in the Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis (FRAME) trial. Despite the varying degrees of fracture risk, Professor McClung pointed out that all 3 trials demonstrated efficacy in reducing fracture risk vs. placebo,9–11 as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Fracture risk reduction versus placebo for osteoanabolic drugs.9–11*

*These are not comparator trials. Entry criteria and patient populations vary.

Adapted from Neer et al. 2001,9 Miller et al. 201610 and Cosman et al. 2016.11

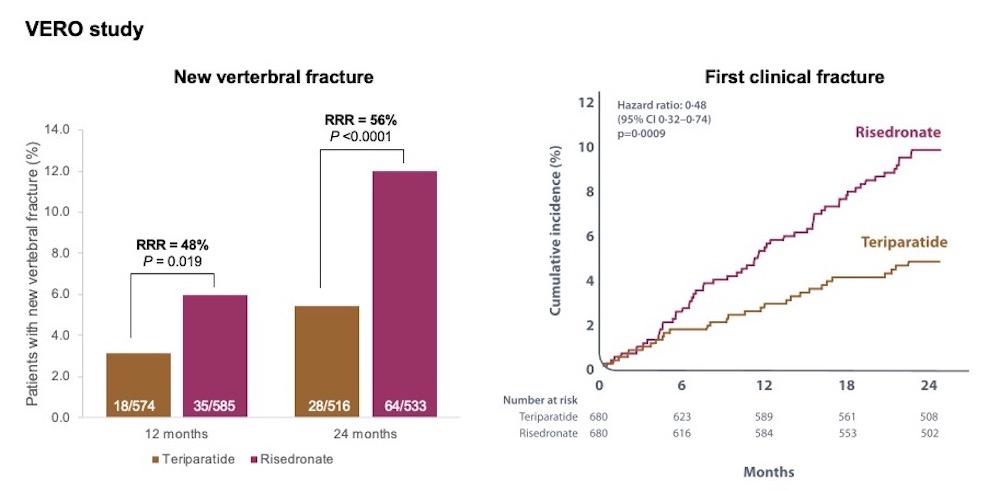

Professor McClung also described data comparing the two osteoanabolic therapies to oral bisphosphonates. The VERO and ARCH trials studied patients at high fracture risk treated with teriparatide vs. risedronate, and high fracture risk treated with romosozumab vs. alendronate, respectively.12,13

The VERO trial of teriparatide (Figure 2), demonstrated reduction in vertebral fracture incidence at 12 and 24 months of 48% and 56% respectively, compared to risedronate.12 Professor McClung noted that “clear divergence in the incidence of the two treatment groups is evident by the end of the first year, and overall the hazard ratio over the two years is 0.48″, in line with previous smaller studies.12 Figure 2 shows data from the double-blind period of the ARCH trial of romosozumab, demonstrating a 37% reduction in the incidence of vertebral fracture in women who received romosozumab, compared to those who received alendronate.13 Professor McClung observed “in the ARCH trial the incidence of non-vertebral fracture shows a separation in the two curves at the 12 month time-point – the curves remained separate even as all patients were switched to the oral bisphosphonate for the remainder of the study”.13

Figure 2. Osteoanabolic therapies vs oral bisphosphonates12,13

Adapted from Kendler et al. 201812 and Saag et al. 2017.13 *Nominal P-values only. NS=not significant.

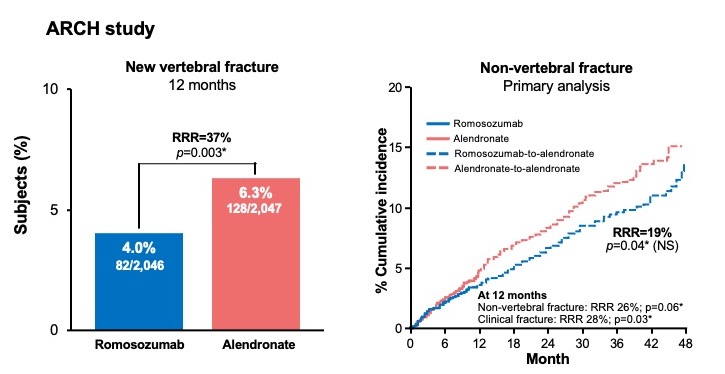

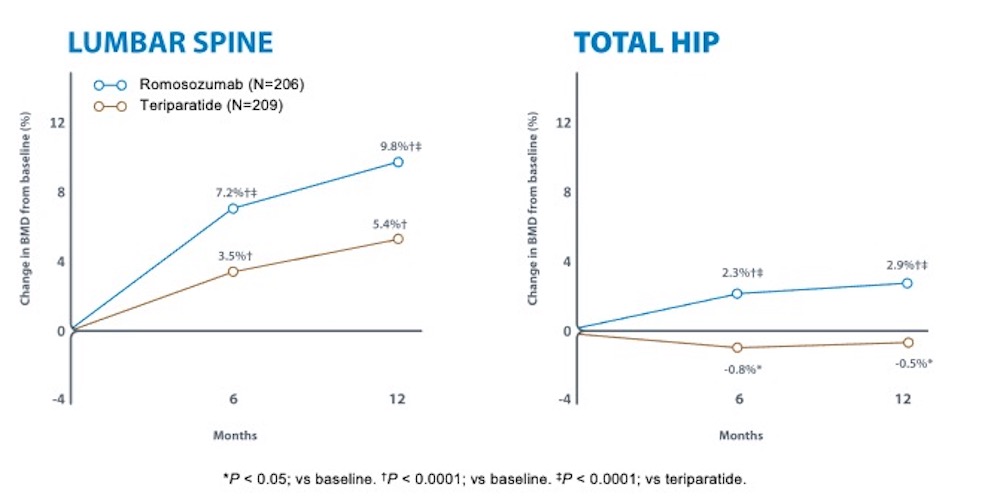

Studies of bone mineral density

Professor McClung also compared the effects of osteoanabolic therapies on bone mineral density (BMD), with a focus on the STRUCTURE study of high risk patients previously treated with bisphosphonates.16 436 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis transitioning from bisphosphonate therapy were randomly assigned to receive romosozumab or teriparatide. As shown in Figure 3, both therapies increased areal BMD in the lumbar spine, but only romosozumab increased areal BMD in the total hip at 12 months.

Figure 3. Areal bone mineral density change from baseline after switching from a bisphosphonate to either teriparatide or romosozumab.16

Adapted from Langdahl et al. 2017.16

Whilst he noted that differences in fracture risk reduction cannot be deduced from the results of the STRUCTURE study, Professor McClung did point out previous associations between larger increases in hip BMD and greater reduction in vertebral and hip fracture risk.17,18 Linking this evidence with the ARCH trial (post-hoc), he stated “these data suggest that the higher the bone mineral density we achieve with therapy, the better the reduction in fracture risk”. He also pointed out that the romosozumab data from the ARCH trial are important because “though interventions with romosozumab are relatively short, i.e. 12 months, they have longer lasting effects even after patients are transitioned to another drug”.13 This information has been taken on board by various societies, underpinning guidance on the appropriate timing of bone building therapy.

Safety of osteoanabolic therapies

The main adverse events of osteoanabolic therapies, as noted by Professor McClung, were hypercalcaemia with teriparatide and injection-site reactions and clinically significant hypersensitivity reactions with romosozumab.10,11,13 He explained that “hypercalcaemia is of course an extension of the mechanism of action of teriparatide”. Serious safety concerns for teriparatide and romosozumab were osteosarcoma and serious cardiovascular events, respectively.7,8

The concern regarding osteosarcoma was clarified by Professor McClung as “based upon studies in rats who received a lifelong dose of therapy, which was associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of osteosarcoma. As a result of this data, the maximum lifetime exposure of patients to teriparatide is limited to 24 months.”7 He went on to outline the Forteo Patient Registry Surveillance Study conducted in the U.S., matching over 75,000 patients treated with teriparatide over 10 years to state registries that recorded cases of osteosarcoma. No matches between the registries were found.14

Data discrepancies between the ARCH and FRAME trials of romosozumab have complicated assessment of the risk of serious cardiovascular events with this agent. An increased risk of positively-adjudicated serious cardiovascular events appeared to occur with romosozumab when compared to oral bisphosphonate in the ARCH trial, but not in the FRAME trial of romosozumab vs. placebo.11,13 Further investigations have not revealed an explanation for this disparity. Professor McClung advised “until we know more about CV risk, it is prudent to use romosozumab in patients at very high risk of fracture and to avoid its use in patients at very high risk for myocardial infarction and stroke, optimising the benefit-risk ratio”.

Australian indications for osteoanabolic therapies

In Australia, both teriparatide and romosozumab are approved for use in osteoporosis. Table 2 shows the specific indications as per the Therapeutic Goods Administration, as well as the PBS reimbursement clinical criteria for each.7,8,15 PBS eligibility for both agents requires treatment by a specialist or a consultant physician.15

Table 2. TGA and PBS criteria for teriparatide and romosozumab.7,8,15

| Teriparatide | Romosozumab | |

| TGA indication |

|

|

| PBS criteria for patients with severe established osteoporosis | Initial treatment:

|

Initial treatment:

|

Continuing treatment:

|

Continuing treatment:

|

Selecting and sequencing osteoanabolic therapy

For the purposes of therapy selection, guidelines by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)/American College of Endocrinology (ACE) and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF)/European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) recommend treating patients according to their fracture risk.1,4 Both groups recommend that bone building therapies such as teriparatide and romosozumab be used to treat those at very high fracture risk.1,4 This is based in part on observations that BMD gains with anabolic agents were significant by as early as 3-6 months in placebo-controlled phase 3 trials of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.7,8 Acknowledging however that some patients under consideration for treatment with an osteoanabolic agent will have already undergone therapy with an antiresorptive, Professor McClung noted evidence showing that “BMD responses to teriparatide and romosozumab are smaller after an antiresorptive agent than in treatment-naïve patients”.11,16,21,22

Summary

For patients with severe established osteoporosis and high fracture risk there are therapies available that rapidly improve bone density and strength and quickly reduce fracture risk.7,8 The osteoanabolic agents teriparatide and romosozumab have been shown to improve trabecular architecture and induce larger gains in BMD and greater reductions in fracture risk when compared to bisphosphonates.7,8 The BMD response is greater when using an osteoanabolic agent before an antiresorptive agent, rather than the reverse.19

International guidelines recommend using osteoanabolic agents in patients at very high risk of fracture, and antiresorptive agents in patients considered high risk of fracture.1–4

References:

- Camacho PM, et al. Endocr Pract. 2020;26 (Suppl 1):1-46.

- Shoback D, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:1-8.

- Eastell R, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622.

- Kanis JA, et al. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31:1-12.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Available at: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/.

- Compston JE, McClung MR and Leslie W. Lancet 2019;393:364-76.

- Forteo® (teriparatide) Approved Product Information. 30 January 2019.

- EVENITY® (romosozumab) Approved Product Information. Available at: www.amgen.com.au/Evenity.PI.

- Neer RM et al. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1434-41.

- Miller PD et al. JAMA 2016;316:722-33.

- Cosman F et al. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1532-43.

- Kendler DL et al. Lancet 2018;391:230–40.

- Saag K et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1417-27. (including supplemental)

- Gilsenan A et al. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32:645-51.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Available at: www.pbs.gov.au.

- Langdahl BL et al. Lancet. 2017;390:1585-94.

- Bouxsein M, et al. J Bone Miner Res 2019;34:632-42.

- Cosman F, et al. J Bone Miner Res 2020;35:1333-42.

- McClung MR. Ageing Clinical and Experimental Research. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01708-8.

- Leder B et al. Lancet. 2015;386:1147-55.

- McClung M et al. Oral presentation at WCO-IOF-ESCEO; Barcelona, Spain; August 20-23, 2020.

Amgen Australia, Level 7, 123 Epping Road, North Ryde, NSW 2113, ABN 31 051 057 428. Phone 1800 649 998 www.amgen.com.au AU-15378 May 2021.