Charles Dickens’ novel A Christmas Carol is renowned as an enjoyable read, but could it also convey an important message for doctors?

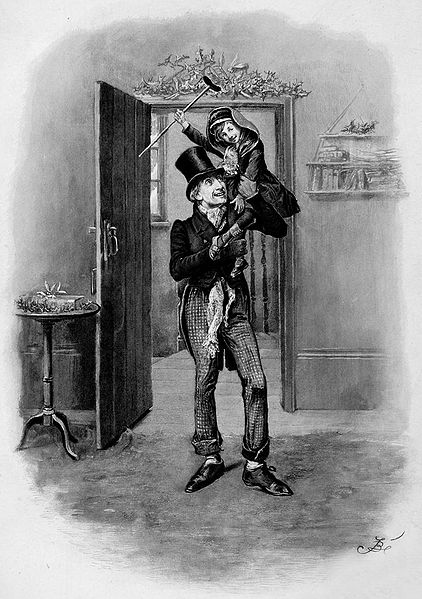

The 1843 classic recounts the story of elderly miser Ebenezer Scrooge, who becomes a better man under the influence of visitations by the spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come.

But it’s the question of what ails the character Tiny Tim that has most frequently drawn the attention of medical readers, with a PubMed search uncovering more than a dozen academic journal articles interrogating the issue.

The most recent of these, authored by Irish paediatrician Dr Ciara O’Neill, points out there are some, albeit limited, clues in Dickens’ text.

The most recent of these, authored by Irish paediatrician Dr Ciara O’Neill, points out there are some, albeit limited, clues in Dickens’ text.

As his name suggests, Tiny Tim is small for his age and underweight (half the size of a prize turkey).

There is no indication of hereditary illness or disability among his parents or five siblings—two brothers and three sisters in the novel.

Elsewhere, it is indicated his orthosis is a single iron frame for both legs. And although mobile with his crutch and able to use both arms, his voice is weak and plaintive and he has at least one withered hand.

“This constellation of clinical phenomena is resistant to a unitary diagnosis, other than through robust use of Crabtree’s bludgeon, a humorous scientific maxim which is that no set of mutually inconsistent observations can exist for which some human intellect cannot conceive a coherent explanation, however complicated,” Dr O’Neill writes in Archives of Disease in Childhood (link here).

Nevertheless, many putative diagnoses have offered in the medical literature over the years.

Common among these type 1 distal renal tubular acidosis, tuberculosis, rickets, scurvy, syphilis, cerebral palsy, spinal dysraphism, muscular dystrophy.

Authors have also taken pains to understand the potential sociological and environmental causes of Tiny Tim’s condition.

As Dr O’Neill points out, some commentators have even tried to link their diagnostic quest to Charles Dickens’ own ailments, particularly kidney disease and nephrolithiasis.

But all of these attempts eventually came to a dead end, she says.

“In the face of the widespread social and environmental inequalities of early Victorian England, Tiny Tim’s condition defies a medical explanation for resolution through better employment prospects for his father, or indeed generous servings of prize turkey,” she writes.

“Perhaps as a profession we have been seduced by the sharp eye of Dickens in his descriptions of over 40 different illnesses in his novels. Some of these accurately described syndromes well before their formulation by clinical medicine.”

Even so, there are nuggets of gold in the text for child health clinicians, particularly the transition from logic to feeling and fantasy in the narrative, Dr O’Neill argues.

“Just as Scrooge is liberated from his hard, logical and unfeeling attitudes towards the poor and disadvantaged and learns to value humanity and warmth, so too can we relax our diagnostic impulses and instead savour the power of this masterpiece to widen our horizons on the human condition.”

She concludes: “As the fates of Tiny Tim reveal, a reflective study of key texts in literature is a potent force to liberate us from a focus on the mechanics of daily clinical practice towards a broader understanding of complexity, paradox and the social dynamics of the world in which we work.”

“If we can accomplish this, then indeed as Tiny Tim concludes at the end of the novel, God might bless us everyone, a sentiment understood and welcomed in a pluralist society of many religions and none.”