Action is needed to address the persisting under-representation of women in cardiovascular clinical trials, a new review shows.

More than two decades after the FDA set up programs to ensure equal participation of women in clinical trials there are still serious gender imbalances in trials of therapies for ischaemic heart disease and heart failure, a study has found.

A review of 36 clinical trials used to support FDA approvals for cardiovascular drugs between 2005 to 2015 found that the average proportion of women enrolled was 34%, with participation rates varying from 22% to 81% in different therapeutic areas.

After adjusting for disease prevalence, women appeared to be reasonably well represented in trials for atrial fibrillation (participation to prevalence ratio 0.8 to 1.1), hypertension (PPR 0.9), and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PPR 1.4);

However women were significantly under-represented in trials of heart failure, for which participation rates for females ranged from 22% to 40%, and the PPR was 0.5 overall.

For coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome/myocardial infarction trials, 24% and 28% of enrolled patients were women, respectively, with a PPR <0.6 in both areas.

The review also found little indication of clinically meaningful gender differences in drug efficacy or safety.

Source: Pilote L, Raparelli V, JACC 2018.

Writing in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the researchers said it was not clear why women were under-represented in some areas of cardiovascular medicine and not others. It was important to identify the barriers to female participation, to make the results relevant at an individual patient level, they added.

“As we move into the era of precision medicine, that is, assessing the impact of a wide range of patient and disease characteristics on drug effects, it is imperative that clinical trial participants represent the full spectrum of patients for whom the drug will be prescribed,” they concluded.

An accompanying commentary said low female recruitment to trials might reflect one-size-fits-all entry criteria modelled on male patterns of heart disease. For example, heart failure trials typically have entry criteria of ejection fraction of <40% and GFR of <30ml/min/1.73m2, which would consistently exclude women.

The same male-biased homogenous criteria might also explain why trials did not show sex differences in outcomes.

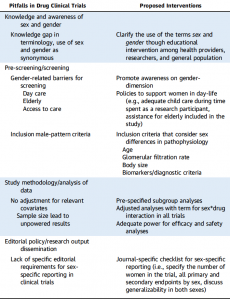

The authors provided a list of six interventions to address low inclusion of women in trials (see table).

“Patients, researchers, and health providers can take action by addressing the alarming gaps in quality and equitable health care for women,” the commentary concluded.

“Our mandate as health providers and researchers should be to catalyse the energy and advance awareness that sex and gender in clinical trials really does matter.”