Prof Richard Macdonnell

The traditional concepts dividing MS into progressive and non-progressive disease are outdated and a potential obstacle to early treatment, according to Professor Richard Macdonell, Director of Neurology, Austin Hospital.

Delivering the E Graeme Robertson Oration at ANZAN 2019 in Sydney, Professor Macdonell said his opinion was that all MS was a progressive disease from the outset, with relapsing remitting MS (RRMS) patients differing from those with primary progressive disease (PPMS) only in having disease activity sufficient to trigger symptoms and new MRI lesions.

“We have grown up with MS being subdivided into these groups which state that there is something different between RRMS and PPMS. I think MS is all one disease –inflammatory – and it’s just the intensity of the inflammation that determines the relapses,” he said.

“I don’t think during the relapsing remitting phase the brain just sits still and is all quiet – I think it’s a state of continuous damaging subclinical inflammation, and it’s just that we don’t have the markers or the skills to detect that.”

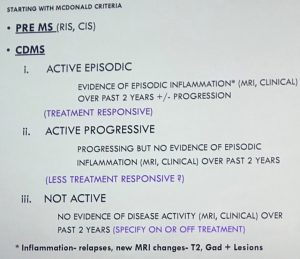

Professor Macdonell said the current criteria for MS were designed by a committee and not always useful in a clinic setting. Instead he preferred to think of patients falling into three groups: active episodic, active progressive and ‘not active’.

The active episodic patients are the ones in whom treatments are likely to have an impact on depressing inflammation, preventing further relapses and slowing the progression of disease, he said.

The active episodic patients are the ones in whom treatments are likely to have an impact on depressing inflammation, preventing further relapses and slowing the progression of disease, he said.

Patients in the active progressive group did not show signs to indicate inflammation, their MRI was pretty stable.

He said patients in the non-active group appeared to be doing but “they are the ones you lose sleep over because you’re not sure what they will look like 10 or 20 years down the line – should I give more aggressive treatment or should I back off? They’re the ones we need to know a lot more about.”

In his talk on the progress and challenges in MS treatment, Professor Macdonell said one of the main advances in the last 20 years was the advent of immunotherapies that allowed early intervention to reduce inflammation and disability in MS.

“It’s a bit like the ‘time is brain’ concept with stroke treatment except we’re looking at months and years instead of minutes,” he said.

“There’s a limited window of opportunity [for treatment]. We do need to start identifying the illness early and start treatment early.”

And while there had been mixed results with individual therapies and variation between patients, the overall picture was that treatment was having an impact in terms of reducing progression of MS and reducing disability.

“We can now definitely treat to reduce relapses, MRI activity and slow accrual of disability in people with MS,” he said.

Recent European cohort studies had shown that people were now entering their 80s with MS and the slowing trajectory of disease meant that many patients do not get to that level of disability in older age, he noted.

The outlook for progressive disease was not so good, but there was still “light on the hill” with treatments such as ocrelizumab and siponimid, said Professor Macdonnell.

These treatments had shown a 12 month shift in disability progression, and ocrelizumab was now awaiting PBS funding.

Looking to the future, the “Holy Grail’ for MS was finding treatments that could promote remyelination, said Professor Macdonnell.

The question was whether drugs such as natalizumab and opicinumab worked by stopping inflammation, neuroprotection or actively promoting axonal repair, he said.